Yer vowels

Yer patterns

What are yers?

- Reflexes of the Common Slavic *ъ, *ь

- Generally reconstructed as [ʊ ɪ], though the reasoning is not always explicit.

- Commonly considered to be ‘reduced’ in quantity and/or quality

- ‘Fleeting’ vowels that synchronically alternate with zero

| Item | Form | Ukrainian | Polish | Slovak | BCMS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘dog’ | NOM.SG | pes | pies | pes | pas |

| NOM.PL | psɨ | psy | psy | psi | |

| ‘dream’ | NOM.SG | son | sen | sen | san |

| NOM.PL | snɨ | sny | sny | sni | |

| ‘coal’ | NOM.SG | węgiel | uhoľ | ugao | |

| NOM.PL | węgle | uhle | ugli | ||

| ‘board’ | NOM.SG | doška | deska | doska | daska |

| GEN.PL | doščok | desek | dosák ~ dosiek | das(a)ka |

Yer patterns: Havlík and Lower

In traditional parlance, yers are either

- Strong, in which case they merge with some other vowel

- Weak, in which case they delete

- Havlík’s Law: weak and strong alternate, starting at the right edge of a sequence

- Lower Rule: a yer is strong before a yer, weak otherwise

- Minor pattern: like Lower, but a yer is weak before a voiceless consonant and a weak yer

Yers and morphology

Common Slavic did not have word-final consonants (or indeed any codas, with very few exceptions). Today’s final consonants generally used to precede a word-final yer: these are weak under all versions of the rule. The yers are often inflectional markers that alternate with full vowels in the paradigm, yielding strong-weak alternations in the stem.

| Case | SG | PL |

|---|---|---|

| NOM | dьnь | dьne |

| GEN | dьne | dьnъ |

| INS | dьnьmь | dьnьmi |

Havlík

The predicted pattern is a zero-vowel alternation site for every yer.

| Pre-Havlík | Havlík | Gloss |

|---|---|---|

| pьs-ъ | pes | ‘dog-NOM’ |

| pьs-a | psa | ‘dog-GEN’ |

| pьs-ьk-ъ | psek | ‘dog-DIM-NOM’ |

| pьs-ьk-a | peska | ‘dog-DIM-GEN’ |

| pьs-ьč-ъk-ъ | pesček | ‘dog-DIM-DIM-NOM’ |

| pьs-ьč-ъk-a | psečka | ‘dog-DIM-DIM-GEN’ |

- Robust in Old Czech, Old Polish, but hardly every found today

- Cz švec ‘cobbler’, GEN.SG ševce; Ukrainian švec’, GEN.SG ševc’a < *šьvьcь

- Slk dom ‘house’, dimunitives domok, domček (cf. Cz domeček)

- Po sejm < sъjьmъ if by levelling from oblique sъjьma etc.

Lower

The predicted pattern is that all yers before a yer vocalize. Note that for the rule to work it has to be applied left to right.

| Pre-vocalization | Lower | Gloss |

|---|---|---|

| pьs-ъ | pies | ‘dog-NOM’ |

| pьs-a | psa | ‘dog-GEN’ |

| pьs-ьk-ъ | piesek | ‘dog-DIM-NOM’ |

| pьs-ьk-a | pieska | ‘dog-DIM-GEN’ |

| pьs-ьč-ъk-ъ | pieseczek | ‘dog-DIM-DIM-NOM’ |

| pьs-ьč-ъk-a | pieseczka | ‘dog-DIM-DIM-GEN’ |

The synchronic consequence is that there can only be one vowel-zero alternation site per paradigm

Segmental patterns of yers

Vocalized yer quality

| Language | *sъnъ ‘dream’ | *dьnь ‘day’ | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ukrainian | son | den’ | ь > e, ъ > o |

| Russian | son | d’en’ | ь > e + C’, ъ > o |

| Belarusian | son | dz’en’ | ь > e + C’, ъ > o |

| Upper Sorbian | són | dźeń | ь > ɛ + C’, ъ > ɔ |

| Lower Sorbian | seń | źeń | ь > ɛ + C’, ъ > ɛ/a |

| Polish | sen | dzień | ь > ɛ + C’, ъ > ɛ |

| Slovak | sen | den | ь > ɛ + C’, ъ > ɛ (but see note) |

| Czech | sen | den | Almost full merger |

| Bulgarian | sъn | den | ь > e, ъ > ъ |

| Macedonian | son | den | ь > e, ъ > o |

| BCMS | san | dan | Full merger |

| Slovenian | sən | dan | Full qualitative merger |

A typology of yer outcomes

We can roughly typologize the qualitative reflexes as follows

- Do the two yers remain distinct in quality?

- Yes: East Slavic, Sorbian, Bulgarian, Macedonian

- No: Polish, Czech, BCMS, Slovenian

- Chaos: Slovak (roughly no in the east and west, yes in the centre)

- Does the front yer soften the preceding consonant?

- Yes: Russian, Belarusian, Polish, Sorbian, (most of) Slovak

- No: Czech (mostly, although there are some traces)

- Irrelevant: Ukrainian, South Slavic

| Vowels alternating with zero | Difference in consonant behaviour | Languages |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple | Yes | Russian, Belarusian, Sorbian: [ɛ ɔ] |

| Slovak: [ɛ ɔ ɑ ɑː i͡e] | ||

| Multiple | No | Bulgarian: [ъ ɛ] |

| Macedonian: [ɛ ɔ] | ||

| Ukrainian: [ɛ ɔ] | ||

| Slovenian: [ə aː] | ||

| One | Yes | Polish: [ɛ] (marginally [ɔ]) |

| One | No | Czech: [ɛ] |

| BCMS: [a] |

Preliminary summary

What does any theory of yers need to explain?

- Why do some vowel alternate with zero and others don’t?

- How do know when to vocalize and when to delete?

- When the yer vocalizes, what quality does it have?

Previous approaches

The Lower rule

Lightner (1965): the Lower rule for Russian

ĭ ŭ \(\rightarrow\) e o / _ C\(_0\) {ĭ ŭ}, applying left to right

The effect is that all yers before a yer vocalize, but the last yer in a sequence, or a yer before a non-yer vowel, do not and can eventually be deleted

The front yer is a normal front vowel and can do everything that front vowels do:

- Palatalize preceding consonants

- Undergo backing once it has merged with /ĕ/

Some Russian derivations

I simplify the detail, especially regarding cyclicity.

| Rule | /dĭn+ĭ/ | /dĭn+ī/ | /dĭn+ĭk+ŭ/ | /dĭn+ĭk+ĭk+ŭ/ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palatalization | dʲĭnʲĭ | dʲĭnʲī | dʲĭnʲĭkŭ | (dʲĭnʲĭk)ĭkŭ |

| Lower | dʲĕnʲĭ | dʲĭnʲī | dʲĕnʲĕkŭ | (dʲĕnʲĕk)ĭkŭ |

| Backing | dʲĕnʲŏkŭ | (dʲenʲŏk)ĭkŭ | ||

| Palatalization | dʲĕnʲŏčʲĭkŭ | |||

| Lower | dʲĕnʲŏčʲĕkŭ | |||

| Yer deletion | dʲĕnʲ | dʲnʲī | dʲĕnʲŏk | dʲĕnʲŏčʲĕk |

| Late rules | dʲenʲ | dnʲi | dʲenʲok | dʲenʲočʲek |

| Gloss | ‘day-NOM’ | ‘day-PL’ | ‘day-DIM-NOM’ | ‘day-DIM-DIM-NOM’ |

Things to note:

- Lower vocalizes all yers except the last one in a sequence: therefore, only the last yer in a sequence will alternate with zero

- Non-vocalized yers are responsible for:

- Word-final soft consonants (d’en’ ‘day’)

- Vocalization of yers before ‘zero suffixes’:

- d’en’-∅ ‘day-SG’ ~ dn’i ‘day.PL’

- d’ev-k-a ‘girl’ ~ GEN.PL d’evok-∅ ~ d’evočka ‘DIM’ ~ d’evoček ‘DIM.GEN.PL’

- Palatalization by suffixes that are consonant-initial on the surface

- d’evočka ‘girl’ \(\leftarrow\) /dēv+ŭk+ĭk+ō/

- kol’ésnik ‘wheelwright’ \(\leftarrow\) /kŏlĕs+ĭn+īk+ŭ/, note lack of backing

Extending the analysis: Polish

In Polish, the vowel alternating with zero is almost always [ɛ]. However, if we posit a back and a front yer we get all the same mileage as we do in Russian; in particular by removing underlying consonant softness

| Rule | /sOn+O/ | /sOn+ɨ/ | /dEn+E/ | /dEn+i/ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palatalization | dʲEnʲE | dʲEnʲi | ||

| Lower | sɛnO | sOnɨ | dʲɛnʲE | dʲnʲi |

| Yer deletion | sɛn | snɨ | dʲenʲ | dʲnʲi |

| Late rules | sɛn | snɨ | d͡ʑɛɲ | dɲi |

Further evidence: secondary imperfective ablaut/tensing

| Vocalized yer | Weak yer | Imperfective | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|

| zapiąć [pʲɔɲ] | zapnę | zapinać | ‘fasten’ |

| nadąć [dɔɲ] | nadmę | nadymać | ‘inflate’ |

Summary of the classical approach

- Why do some vowel alternate with zero and others don’t?

They are featurally different in the underlying representation

- How do we know when to vocalize and when to delete?

The Lower rule is sensitive to the features of vowels in the following syllable

- When the yer vocalizes, what quality does it have?

Determined by the Lower rule

Some more questions we might ask

- Do we need these highly abstract URs and absolute neutralization rules?

- Where is the phonotactics of consonant clusters in all this?

- If the quality of vocalized yers is only up to the Lower rule, why are they (almost) always identical to some other vowel?

Autosegmentalizing Lower

With the advent of autosegmental phonology, the property of ‘alternating with zero’ could be encoded by means other than segmental features

What does this get us?

- Any vowel can be a yer: East Slavic, Sorbian, especially Slovak (Rubach 1993), even Polish

- No special ‘yer subinventory’: yers are featurally regular

- What is special about yers is prosodic position

- CVCV phonology: alternation with zero follows from first principles

- CVCV phonology: clearly articulated link with phonotactics

Phonotactics, deletion, and insertion

Deletion or insertion?

In principle, vowel-zero alternations can be due to either deletion or insertion

- The standard account relies on deletion

- Why not insertion? Two reasons

- Phonotactics

- Vowel quality

Insertion and phonotactics

- Insertion could be driven by

- Avoidance of bad sonority profiles

- Avoidance of consonant clusters (at word edges) tout court

Yers and cluster avoidance

- Classic examples aiming to show an absence of general cluster avoidance

- Russian laska ‘stoat’ ~ lasok ‘GEN.PL’ vs. laska ‘tenderness’ ~ lask ‘GEN.PL’

- Russian z’erno ‘grain’ ~ z’or’en ‘GEN.PL’ vs. s’erna ‘chamois’ ~ s’ern ‘GEN.PL’

- Polish trumna ‘coffin’ ~ trumien vs. kolumna ‘column’ ~ kolumn ‘GEN.PL’

- Slovak octu ‘vinegar.GEN.SG’ ~ ocot ‘NOM.SG’ vs. pocta ‘distinction’ ~ pôct ‘GEN.PL’

Yers and sonority profiles

- Classic examples showing that suboptimal sonority profiles are tolerated

- Russian t’eatr ‘theatre’, os’otr ‘sturgeon’

- Polish wiatr ‘wind’, cyfr ‘figure.GEN.PL’

However…

- In BCMS1 only coronal fricative-stop clusters are allowed word-finally

- Everything else is broken up by a vowel, leading to alternations

- The only vowel involved is [a]

- vjetar ~ vjetru ‘wind’ like sladak ~ slatki ‘sweet’

- There is a plausible insertion analysis

1 In the native lexicon… there are loanword and other complications

Sonority and epenthesis

At least historically, in many languages word-final rising-sonority clusters were partially or fully removed by epenthesis. This leads to vowel-zero alternations basically indistinguishable from those involving historical yers

- BCMS vjetar ‘wind’, oštar ‘sharp’ ~ vjetri, oštri

- Bulgarian ogъn ‘fire’, ostъr ‘sharp’ ~ ogn’ove, ostri2

- Russian v’et’er ‘wind’, ogon’ ‘fire’, v’ód’er ‘bucket.GEN.PL’ ~ v’etrɨ, ogn’i, v’ódra (Isačenko 1970)

- On the other hand, m’etr ‘metre’

2 Bulgarian in general has quite restricted syllable phonotactics.

Why not both?

| Language | UR | NOM.SG | GEN.SG | DIM | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polish | /t͡sɨfr/ | cyfra | cyfr | cyferka | ‘figure’ |

| /srebEr/ | srebro | sreber | sreberka | ‘silver’ | |

| Russian | /igl/ | igla | igl | igolka | ‘needle’ |

| /kukOl/ | kukla | kukol | kukolka | ‘doll’ |

- In the GEN.SG, we find regular yer vocalization. If there is no yer underlyingly, there is no vowel

- In the DIM, we find a vowel even if there is no yer, likely for phonotactic reasons

When a vowel is inserted, its quality should be predictable

Yers and predictability: Russian

Is yer quality predictable?

- Scheer (2011) passim, and many others: no

| Context | e | o |

|---|---|---|

| Cʲ_ | d’en’ ~ dn’a ‘day’ | l’on ~ l’na ‘linen’ |

| C_ | * | son ~ sna ‘dream’ |

Remember that e after hard consonants (excluding the historically soft š ž c) is not usual

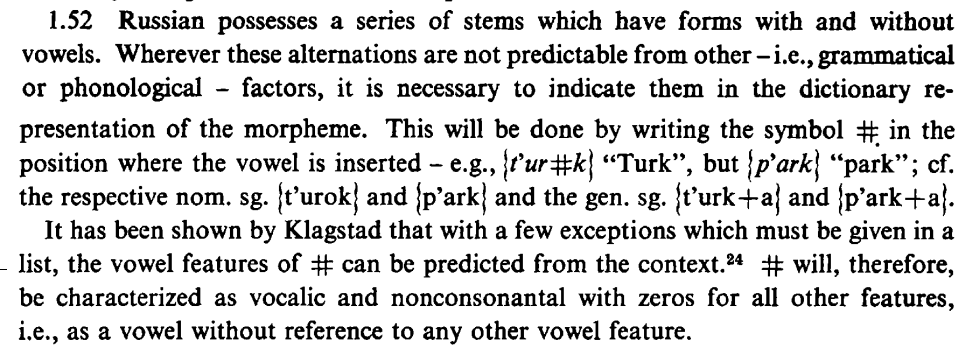

Halle (1959) referring to Klagstad (1954): yes

Like other aspects of the pre-1960s approach, this view survived in Slavic circles (e.g. Townsend 1975; Hamilton 1976; Hamilton 1980)

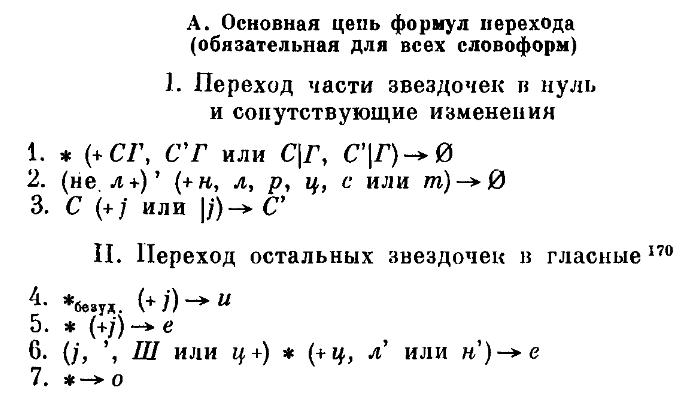

Zaliznyak (1967): yes (essentially)

What this is a set of deterministic rules that rewrite an asterisk (an alternation site) to a vowel or zero.

The return of the mid vowel alternation

- After a hard consonant, the yer is always [o]

- After a soft consonant, the yer is either [e] or [o]

- In the classical analysis, this is backwards: the soft consonant is soft because the yer is front

- The sequence [Cʲo] from /Cĭ/ arises by the sequence of Palatalization > Lower > Backing

An alternative

So, unpredictable after all?

- Yesterday we developed an account of the e ~ o alternation mostly allowed us to cope with exceptionality

- Two classes of mid vowel after [Cʲ]

- [e] before a softening suffix, [o] elsewhere

- Non-alternating [e]

As with the stable e ~ o alternation, we need to remember that spelling is an unreliable guide: we can only know the quality of the yer after a soft consonant reliably when it is stressed.

- It turns out that when a vowel alternates with zero, it is overwhelmingly type 1

- The exceptions are either conditioned (before j c l’ n’)3 or tiny in number: in the nouns, there is a total of five exceptions (Zaliznyak 1967; Iosad 2020). I can live with that.

3 Cf. zem’él’ ‘earth.GEN.PL’, s’em’éj ‘family.GEN.PL’ from zeml’a, sem’ja with a non-softening suffix.

Summing up

- The quality of Russian yers is mostly predictable if

- We take into account the softness of the preceding consonant

- We adapt our analysis of mid vowels: when the right context drives the choice, the front outcome is conditioned and the back outcome is the elsewhere

- We still (mostly) cannot predict when the vowel is inserted or not

Conclusion

Why does this matter?

I have not focused here on the very tough problem of what makes the yers vocalize or not. Instead, I would like us to think about what this analysis tells us about the viability of the standard approach.

- The analysis relies on consonant softness being present before yer quality is resolved: ‘consonant power’

- This is incompatible with the classical account, where the consonant is soft because the yer is front: ‘vowel power’

- Who is right?

Consonant power revisited

- In the consonant power approach

- Consonant softness can be underlying

- Palatalization is not a sure-fire sign of an underlying front vowel

- Repeated attempts to resurrect this in the generative tradition (Farina 1991; Boyd 1997; Padgett 2011) have not been too influential

- Vowel power continues to rule the roost (Halle & Matushansky 2002; Rubach 2000; Rubach 2005; Rubach 2016)

One final prediction

Scheer (2012): ‘if a vowel is epenthetic, its quality cannot be contrastive’

| NOM.SG | GEN.PL | Derivative | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|

| igla | igl | igólka | ‘needle’ |

| iskra | iskr | ískorka | ‘spark’ |

| nasmork | násmoročnɨj | ‘cold’ | |

| pol’za | pol’z | pol’éznɨj | ‘useful’ |

| vojna | vojn | vojénnɨj | ‘war’ |

| korabl’ | korab’él’nɨj | ‘ship’ | |

| s’el’d’ | s’el’ódka | ‘herring’ |

- The vowels are not yers — but they follow the generalizatons quite precisely

- The softness of the consonants determines the quality of the vowels, not the other way around

There are a couple of counterexamples here, namely v’eng’érka ‘Hungarian woman’ (v’engr ‘Hungarian man’), noted by Scheer (2010b), and šl’ax’etsk’ij ‘belonging to the szlachta’ (šl’axta ‘szlachta’), where the soft velars are likely due to the following front vowel, not the other way around. Both are Polish borrowings and are plausibly stored exceptions.

In order to salvage the postulate that consonant softness always comes from a front vowel, the classical approach is forced to stipulate the quality of the epenthetic vowel.

What’s next?

Tomorrow, we reconsider the status of the historically informed traditional approach.