Slavic languages and (generative) phonology

Setting the scene

In this course, we adopt the broadly generative perspective on what counts as ‘phonology’. Some of you may be familiar with other traditions, especially those indebted to structuralist frameworks like the Prague School, or one of the Soviet schools of phonology.

If you would like to know about more structuralist approaches to phonology, the freely available Anderson (2021) tells the story in more detail. I offer a more focused overview of Soviet frameworks in Iosad (2022); a preprint version is here. I also recommend Fischer-Jørgensen (1975) (available online via this page) for an excellent history that is not written from a generative-centric perspective.

In structuralist phonology, the key notion is the phoneme, which may have more than one allophone, and the aim of the analyst is to describe an utterance in phonemic terms. Different theoretical frameworks use different approaches on how to phonemicize utterances. The central empirical facts are usually distributions, which determine whether a pair of elements belong to the same phoneme or not.

In generative phonology — normally associated with Chomsky & Halle (1968), although we will revisit this — the key aim is to identify the underlying representation and the rules that derive observed surface representations from them. While distributions play a role, the analytical emphasis is on alternations, because they directly demonstrate the action of rules.

What counts as phonology?

- Distributions

- Allophonic alternations

- Neutralizing alternations

- Morphophonology

Distributions and allophony: Bulgarian vowels

| Phoneme | Stressed | Unstressed | Alternation |

|---|---|---|---|

| /a/ | ˈɡlaven ‘main’ | ɡlɐˈva ‘head’ | [a] ~ [ɐ] |

| /ɛ/ | ˈvrɛme ‘time.SG’ | vremeˈna ‘time.PL’ | [ɛ] ~ [e] |

| /ɔ/ | ˈkɔsəm ‘hair’ | kosˈmat ‘hairy’ | [ɔ] ~ [o] |

| /i/ | ˈtip ‘type’ | tiˈpɤt ‘type.DEF’ | [i] |

| /u/ | ˈkupʲə ‘buy.PRS.1SG’ | kuˈpuvɐm ‘buy.IPFV.PRS.1SG’ | [u] |

| /ə/ | ˈɫɤk ‘bow’ | ləˈkɤt ‘bow.DEF’ | [ɤ] ~ [ə] |

For the traditional view, see Tilkov (1982); for a detailed recent empirical study, see Sabev (2023).

The pairs [a] ~ [ɐ], [ɛ] ~[e] etc. are in complementary distribution determined by stress. In structuralist phonology, we say they belong to the same phoneme; the basic variant is the one found in stressed syllables.

In generative phonology, we say that the unstressed variants derive by a rule that applies in unstressed position. In stressed syllables, no rule applies and the vowel in the underlying representation surfaces unchanged. Because stress in Bulgarian is mobile, this machinery creates alternations where the same morpheme occurs in different shapes depending on where stress falls: [ɡlav] ~ [ɡlɐv], [mɔr] ~ [mor] etc. These are allophonic1 alternations, because the alternating segments do not contrast underlyingly.

1 Or ‘non-neutralizing’

Neutralizing alternations: Bulgarian soft consonants

Most Bulgarian consonants come in hard (plain) and soft (palatalized) versions, which contrast before back and central vowels.

| Following vowel | Hard | Soft |

|---|---|---|

| [a] | baɫ ‘ball’ | bʲaɫ ‘white’ |

| [ɤ] | ɡlɐˈsɤt ‘voice.DEF’ | ɡlɐˈsʲɤt ‘read.PRS.3PL’ |

| [u] | kup ‘pile’ | kʲup ‘cauldron’ |

| [ɔ] | poˈzɔr ‘shame’ | poˈzʲɔr ‘poseur’ |

Word-finally, only hard consonants are allowed. Many lexical items alternate accordingly.

| Word-final | Prevocalic | Gloss |

|---|---|---|

| sɤn | səˈnʲɤt | ‘dream’ |

| kɔn | ˈkɔnʲət | ‘horse’ |

| kraɫ | ˈkralʲət | ‘king’ |

| vaɫ | ˈvaɫət | ‘rampart’ |

| zvɤn | zvəˈnɤt | ‘peal’ |

| trɔn | ˈtrɔnət | ‘throne’ |

These alternations involve the pairs [n] ~ [nʲ], [ɫ] ~ [lʲ], which are otherwise distinct phonemes in the language. These are neutralizing alternations. In this case, the outcome of the neutralization is unambiguous: it is the hard consonant. Structuralist schools differ in their analysis of these, but the critical property is that they are obligatory — that is, they occur whenever the context is met. For this reason they can be called automatic.

Morphophonological alternations: Bulgarian palatalization

Before the front vowels [ɛ i], the hard-soft contrast is neutralized. For most consonants, the outcome is analysed as hard.2

2 We will revisit this

| Contrast | Neutralization | Gloss |

|---|---|---|

| bʲaɫa | bɛli | ‘white.FEM.SG ~ PL’ |

| banʲa | bani | ‘bath.SG ~ PL’ |

| nʲama | nemi | ‘mute FEM.SG ~ PL’ |

| zɛmʲa | zɛmi | ‘earth.SG ~ PL’ |

Velar consonants neutralize to soft in the same context, with alternations.

| Hard | Soft | Gloss |

|---|---|---|

| dəˈɡa | dəˈɡʲi | ‘arc’ |

| ˈbitka | ˈbitkʲi | ‘battle’ |

| ˈɔrex | ˈɔrexʲi | ‘walnut’ |

But other [i ɛ] suffixes do different things.

| Hard | Palatalization I | Palatalization II |

|---|---|---|

| vɤɫk ‘wolf’ | ˈvɤɫt͡si ‘PL’ | ˈvɤɫt͡ʃi ‘ADJ’ |

| ˈpɔdviɡət ‘feat.DEF’ | ˈpɔdvizi ‘PL’ | podˈviʒen ‘movable’ |

| siroˈmax ‘pauper’ | siroˈmasi ‘PL’ | siromɐˈʃija ‘poverty’ |

In structuralist phonology, such alternations are generally considered morphophonological3 and usually considered to be different in kind to allophony and obligatory neutralization.

3 Sometimes also historic, or non-automatic to distinguish from automatic neutralization.

Slavic phonology and phonological theory

All of these types of alternations are pervasive across the Slavic languages. A lot of Western phonological theory was developed in Slavic-speaking countries, and had to deal with all of these issues. I would argue that in fact these properties of the Slavic languages were a key, and perhaps underappreciated, driver in the development of many flavours of phonology — including generative phonology.

As we will see, a lot of theory development has centred Russian. This undoubtedly reflects the dynamics of political and cultural power, and we should reflect on that. Russian is also a relatively conservative language with regard to sound change, and that is in some respects an advantage in the context of phonology, for reasons that will become clear soon. To what extent Russian-focused scholarship has occluded the patterns is a theme we will keep returning to.

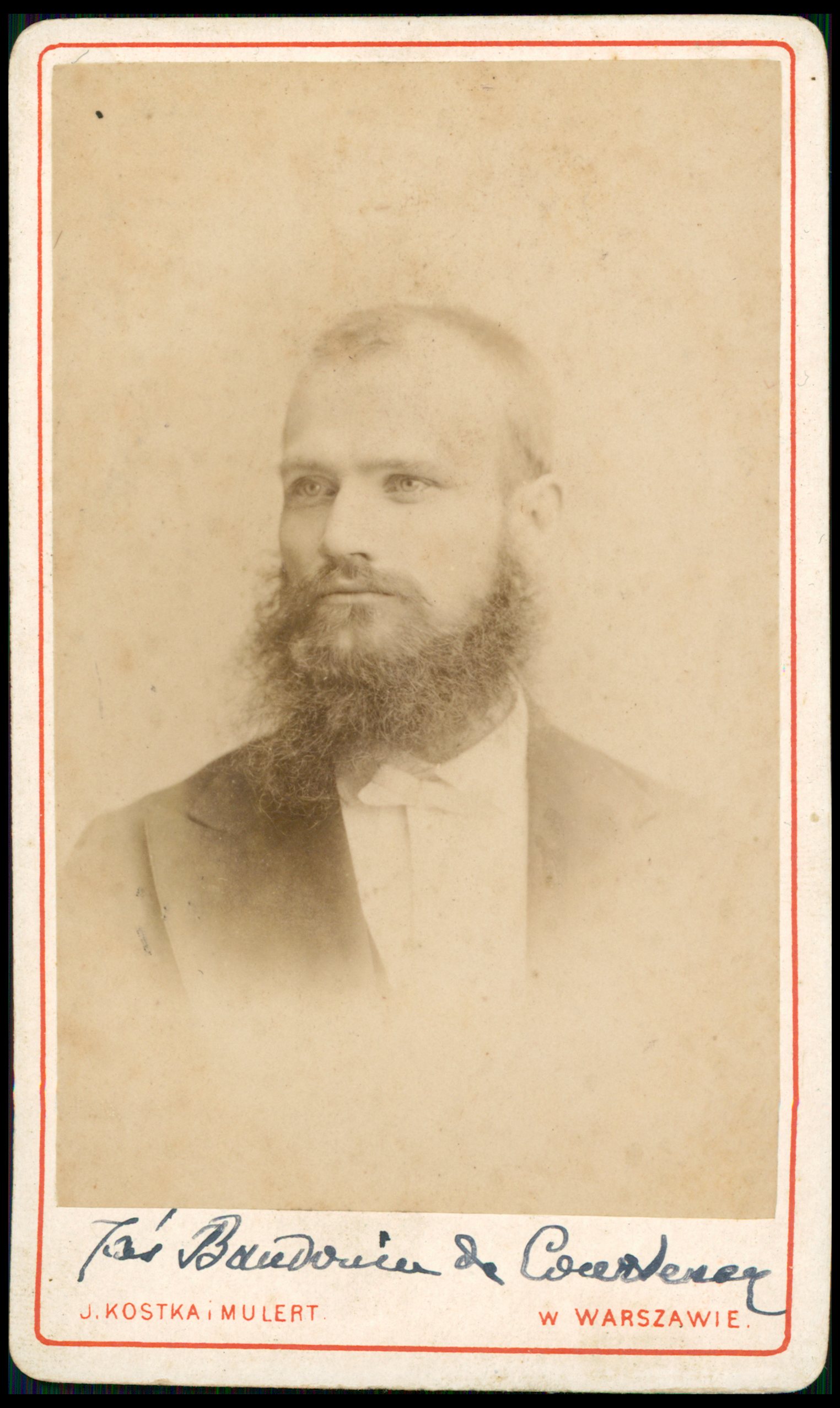

The beginnings: The Kazan School

The Kazan phonologists (who were Poles working, at least to start with, in Imperial Russia) are usually credited the idea of the phoneme as an abstract representation distinct from the phonetic substance, but did not yet link it very explicitly to contrast. They did pay a lot of attention to alternations, and especially the distinction between live/automatic and historical/non-automatic, where Polish and Russian provided fertile ground.

The St Petersburg (Leningrad) School

Lev Shcherba is usually credited for developing lexical distinctiveness as the basis for defining the phoneme. He worked in Russia, and focused a lot on Russian; he also had a strong background in Slavic phonology, having written a thesis on a Sorbian dialect. His primary interest was in phonetics: alternations and neutralization were not as central to his theoretical approach.

Moscow to Prague: Nikolai Trubetzkoy

Members of the Prague Linguistic Circle, including Trubetzkoy and (especially) Jakobson themselves, had wide-ranging interests beyond phonology and indeed linguistics, but here we focus on the phonology part. For a book-length treatment of the Prague Circle, see Toman (1995); I also recommend Sériot (2014) for the intellectual background.

Among theoretical phonologists, Nikolai Trubetzkoy is widely seen as the founding father of classic structuralist phonology, for his Principles of phonology (Trubetzkoy 1939). His interests were strongly focused on Slavic philology generally: a new historical grammar of the Slavic languages was his unfinished magnum opus (see also Trubetzkoy 1954). Trubetzkoy’ intellectual background is linked to Moscow, where he trained before leaving the country.

A notable feature of Trubetzkoy’s approach is the strict separation between allophonic alternation, automatic neutralization (implemented by positing underspecified archiphonemes), and morphophonology, considered to be a separate component of grammar. The theory of non-automatic alternations remained relatively underdeveloped (but see Trubetzkoy 1934), but it is clear that for him it is different in kind from automatic phonology.

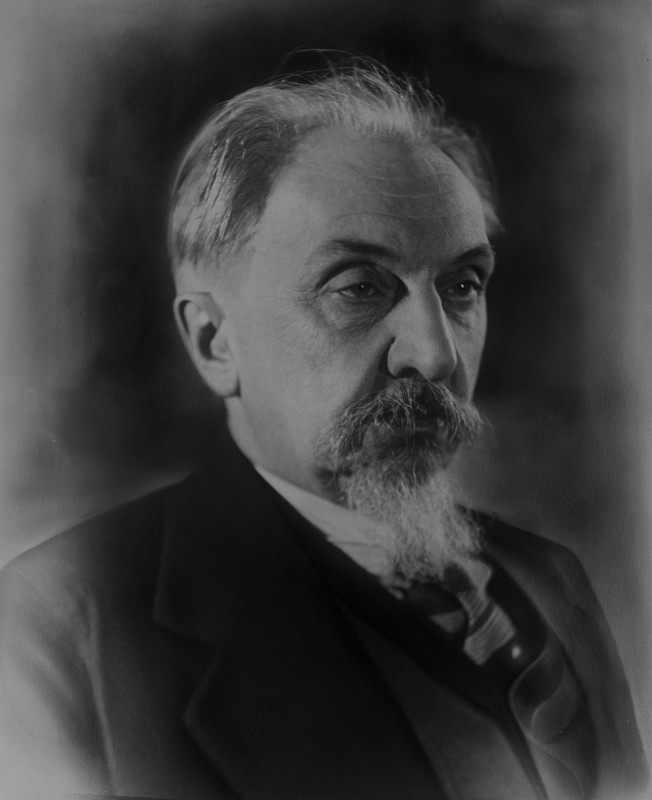

Moscow to Prague to Harvard: Roman Jakobson

Another product of Moscow, Jakobson was Trubetzkoy’s close collaborator in Prague, where he stayed until the start of the war. He made significant contributions to the analysis of Russian, Czech, and Serbo-Croatian phonology within the Praguian mould. After the war, he moved to the US and developed his theory in new directions.

In earlier work, Jakobson, like Trubetzkoy, was interested in the relationship of elements within an individual system. This can be seen in his highly influential Remarks on the phonological development of Russian compared to the other Slavic languages (Jakobson 1929), which offered an early example of Praguian phonological analysis and has been hugely influential in the synchronic and diachronic phonological analysis of the Slavic languages ever since.

Later, Jakobson became interested in information theory and the notion of ‘efficiency’ (see Dresher & Hall 2022). This led him towards developing more abstract analyses that were not limited to observing surface patterns of contrast and neutralization. A key moment was the publication of Russian conjugation.

The Russian conjugation moment

The traditional analysis of Slavic verbal inflection posits two stems (the infinitive stem and the present-tense stem) for each verb. Their distribution across the paradigm is seen as purely morphological. How the shapes of the two stems are related is also not predictable: it is a lexical property of the verb.

| Infinitive stem | Present-tense stem | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infinitive | plaka-t’ | Present tense | 1SG | plač-u | |

| Past tense | SG.M | plaka-l | 2SG | plač-e-š | |

| SG.F | plaka-l-a | 3SG | plač-e-t | ||

| SG.N | plaka-l-o | 1PL | plač-e-m | ||

| PL | plaka-l-i | 2PL | plač-e-te | ||

| Past participle | plaka-vš- | 3PL | plač-ut | ||

| (za)plaka-nn- | Imperative | 2SG | plač | ||

| Present participle | plač-ušč- | ||||

- In some verbs, the infinitive stem is formed by adding a vowel to the present-tense stem: plakat’ ~ plaču

- In other verbs, the infinitive stem is formed by truncation of the present-tense stem: dela-t’ ~ delaj-u ‘do’

- In yet others, both end in a consonant: nes-ti ~ nes-u ‘carry’

The general case:

- The ‘infinitive’ stem ends in a vowel and precedes consonant-initial suffixes

- The ‘present-tense’ stem ends in a consonant and precedes vowel-initial suffixes

All forms are derived from a single stem by applying a sequence of rewrite rules, notably deletion of a vowel before a vowel and deletion of a consonant before a consonant.

| Verb | Infinitive stem | Present-tense stem |

|---|---|---|

| ‘cry’ | plaka-ti → plakat | plak |

| ‘do’ | dela |

delaj-u → delaju |

| ‘carry’ | nes-ti → nesti | nes-u → nesu |

The palatalization k → č (and others like it) occurs before a deleted stem vowel

This analysis has two properties of historic importance:

- The alternations in question sit firmly within the ‘historic’ (morphophonological) sphere: European structuralists did not really consider this to be phonology4

- Efficiently capturing generalizations takes precedence over sticking to surface patterns

4 It is probably not a coincidence that in this paper, written soon after his move to the US, Jakobson approvingly cites Bloomfield, who dealt with morphophonology in the languages of North America using rewrite rules. For more on the links between generative phonology and North American ‘descriptivism’, see Goldsmith (2008).

Riga to Harvard to MIT: Morris Halle

Morris Halle worked under Jakobson, and some of his earliest work is directly developing Jakobson’s new approaches, such as his Old Church Slavonic conjugation. The approach based on rewrite was front and centre in his Sound pattern of Russian, a work now not much read, but often seen as a precursor to the Sound pattern of English.

With the basic structure of the verbal paradigm being very similar across the Slavic languages, the Jakobsonian generalization was widely applicable to other languages. In applying the method to Old Church Slavic, Halle (1951) discovered more rules that unified apparently disparate stems. Crucially, what such rules often did was reproduce the diachronic development.

| Verb | Stem | Infinitive | PRS.1SG | AOR.3SG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘cut’ | rěza- | rěza-ti | rěž |

rěza- |

| ‘know’ | znaj- | zna |

znaj-ǫ | zna |

| ‘lead’ | ved- | ved-ti → vesti | ved-ǫ | ved-e- |

| ‘cook’ | pek- | pek-ti → pešti | pek-ǫ | pek-e- |

| ‘curse’ | klьn- | klьn-ti → klęti | klьn-ǫ | klьn- |

| ‘blow’ | dъm- | dъm-ti → dǫti | dъm-ǫ | dъm- |

Expanding the scope of phonology

Arguably the more famous innovation by Halle was the analysis of voicing assimilation in Russian, originally presented in a talk entitled On the phonetic rules of Russian and reproduced in Halle (1959).

Russian shows final devoicing and voicing assimilation of obstruents across word boundaries. In most cases, the alternations we observe involve segments that are otherwise different phonemes: they are automatic neutralizing alternations. The affricates [t͡ʃʲ] and [t͡s] lack phonemic voiced counterparts, but still undergo assimilation: for these segments, the alternations are allophonic. However, they are patently the same process, so splitting them into two alternations — one neutralizing and one allophonic — misses the generalization.

| Gloss | Word-final | Prevocalic | Assimilation context | Alternation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘cat’ | kɔt | kɐˈtˠi | kɔd bˠi | /t/ ~ /t/ ~ /d/ |

| ‘code’ | kɔt | ˈkɔdˠi | kɔd bˠi | /t/ ~ /d/ ~ /d/ |

| ‘night’ | nɔt͡ʃʲ | ˈnɔt͡ʃʲi | nɔd͡ʒʲ bˠi | /t͡ʃʲ/ ~ /t͡ʃʲ/ ~ /t͡ʃʲ/ [d͡ʒʲ] |

It is commonly assumed that this was the killer argument against the ‘taxonomic phoneme’, which convinced phonologists (in North America at least) that derivational accounts aiming to capture generalizations without regard to surface contrast or phonemic status are superior to earlier approaches.

This is a little bit of a myth: see Anderson (2000) on the contemporary reception of Halle’s work, Kiparsky (2018) on the fact that the duplication identified by Halle was well known prior to his analysis, and Dresher & Hall (2020) on the wider repercussions. Still, Halle’s analysis of Russian remains central to the history of the field.

- Premise: the grammar consists of rewrite rules

- Premise: rewrite rules handle historical alternations, live neutralizing alternations, and allophony

- Premise: rules responsible for allophony manipulate phonological units

- Conclusion: rewrite rules manipulate phonological units

The classic generative approach to Slavic phonology

For the rest of the week, we will look at some specific examples of how Slavic languages were analysed by generative phonologists from the early 1960s onwards.

- Large premium on generality and economy

- Wide empirical scope: aim for a comprehensive analysis of all kinds of patterns within the same system

- In practice: underlying representations that reproduce earlier historical stage, rules that recap the diachronic development

In many ways, this is not really surprising: today’s irregular morphology is often yesterday’s regular sound change, so an economical account that captures all the generalization often is the diachronic one.

This was a feature, not a bug! The fact that underlying representations stuck closely to earlier stages was treated as a discovery: URs changed more slowly than surface representations.

The received analysis

From Slavic phonology to generative phonology

- Further work on Slavic itself (Halle 1963; Lightner 1963; 1965)

- Programmatic development of the approach (Halle 1962)

- Incorporation of links to new syntactic theories through notions like immediate constituency analysis and the cycle (Halle 1963; Lightner 1967)

- Chomsky & Halle (1968) as the crystallization of the generative approach to phonology

SPE is often treated as ushering in a Kuhnian scientific revolution — a paradigm shift that made what came before it largely irrelevant to the conduct of ‘normal science’. Is it true?

From a Slavic perspective, SPE most certainly did not cut short the development of the Trubetzkoy — Jakobson — pre-SPE Halle line. In the guise of a ‘morpho-phonological’ approach, it remained arguably the mainstream view of phonology in Slavonic studies departments in North America for a long time, and remains strong even now. For some reflections from the Slavic side, see Flier (1974), Shapiro (1974), or Sussex (1976). For views from the generative side, see Bethin (2006) and Kavitskaya (2017).

All week, I will argue that most non-specialist phonologists who have dealt with Slavic have really dealt with the Jakobson-Halle-Lightner version of it, and this is something we should problematize more.

Lightner vs. Modern Standard Russian

To give you a sense of this approach, here is the general picture of the Russian vowel system in Lightner (1965).

If this looks familiar to you from Slavic historical phonology… you’re not wrong.

| Surface vowel | Underlying vowel | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| [i] | /ī/ | |

| /ū/ | Fronting in some contexts | |

| [ɨ] | /ū/ | |

| [u] | /ou/ | |

| /eu/ | Source of surface [Cʲu] | |

| /oN/ | When nasal is syllable-final | |

| [e] | /ĕ/ | When not → [o] | |

| /ĭ/ | By the Lower rule for yers, when not → [o] | | |

| /ē/ | When not alternating with o | |

| [o] | /ŏ/ | |

| /ŭ/ | By the Lower rule for yers | |

| /ĭ ĕ/ | When subject to e → o | | |

| [a] | /ō/ | |

| /ē/ | In cases like kričat’ ‘shout’ /krīk-ē-tī/ | |

| /eN iN/ | When nasal is syllable-final; source of surface [Cʲa] |

Here are some underlying representations:

| SR | UR | Gloss |

|---|---|---|

| žog | gĭg-l-ŭ | burn-PST-SG.M |

| žgla | gĭg-l-ō | burn-PST-SG.F |

| pisat’ | pīs-ō-tī | write-INF |

| pišu | pīs-ō-ĕ-m | write-PRS.1SG |

| načat’ | nō-kĭn-tī | begin.PFV-INF |

| načnët | nō-kĭn-ĕ–t | begin.PFV-PRS.1SG |

| načinat’ | nō-kīn-ō-tī | begin.IPFV-INF |

And here is a real derivation:

- Pre-cyclic rule: /(plōt+ī+ī)+m/ → ((plōt+ī+u)+m)

- First cycle: (plōt+ī+u) → (plōt+ju) → (plōtʲ+j+u)

- Second cycle: (plōtʲ+j+u+m) → (plōtʲ+ū+m) → (plōtʲ+j+ū) → (plōčʲū) → [plačʲu]

Although this seems extreme, the basic idea proved remarkably resilient. Tomorrow, we look at consonant palatalization.