Yer vowels

Plan for today

- Yer patterns, Havlík and Lower

- Segmental yer patterns across Slavic

- Lower, deletion and insertion

- Yers, palatalization, and mid vowel alternations

Yer patterns

What are yers?

| Item | Form | Ukrainian | Polish | Slovak | BCMS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘dog’ | NOM.SG | pes | pies | pes | pas |

| NOM.PL | psɨ | psy | psy | psi | |

| ‘dream’ | NOM.SG | son | sen | sen | san |

| NOM.PL | snɨ | sny | sny | sni | |

| ‘coal’ | NOM.SG | węgiel | uhoľ | ugao | |

| NOM.PL | węgle | uhle | ugli | ||

| ‘board’ | NOM.SG | doška | deska | doska | daska |

| GEN.PL | doščok | desek | dosák ~ dosiek | das(a)ka |

Yer patterns: Havlík and Lower

In traditional parlance, yers are either

- Strong, in which case they merge with some other vowel

- Weak, in which case they delete

Two main patterns and a minor one

- Havlík’s Law: weak and strong alternate, starting at the right edge of a sequence

- Lower Rule: a yer is strong before a yer, weak otherwise

- Minor pattern: like Lower, but a yer is weak before a voiceless consonant and a weak yer

Yers and morphology

| Case | SG | PL |

|---|---|---|

| NOM | dьnь | dьne |

| GEN | dьne | dьnъ |

| INS | dьnьmь | dьnьmi |

Havlík

| Pre-Havlík | Havlík | Gloss |

|---|---|---|

| pьs-ъ | pes | ‘dog-NOM’ |

| pьs-a | psa | ‘dog-GEN’ |

| pьs-ьk-ъ | psek | ‘dog-DIM-NOM’ |

| pьs-ьk-a | peska | ‘dog-DIM-GEN’ |

| pьs-ьč-ъk-ъ | pesček | ‘dog-DIM-DIM-NOM’ |

| pьs-ьč-ъk-a | psečka | ‘dog-DIM-DIM-GEN’ |

- Robust in Old Czech, Old Polish, but hardly every found today

- Cz švec ‘cobbler’, GEN.SG ševce; Ukrainian švec’, GEN.SG ševc’a < *šьvьcь

- Slk dom ‘house’, dimunitives domok, domček (cf. Cz domeček)

- Po sejm < sъjьmъ if by levelling from oblique sъjьma etc.

Lower

| Pre-vocalization | Lower | Gloss |

|---|---|---|

| pьs-ъ | pies | ‘dog-NOM’ |

| pьs-a | psa | ‘dog-GEN’ |

| pьs-ьk-ъ | piesek | ‘dog-DIM-NOM’ |

| pьs-ьk-a | pieska | ‘dog-DIM-GEN’ |

| pьs-ьč-ъk-ъ | pieseczek | ‘dog-DIM-DIM-NOM’ |

| pьs-ьč-ъk-a | pieseczka | ‘dog-DIM-DIM-GEN’ |

Synchronic corollary

The synchronic consequence is that there can only be one vowel-zero alternation site per paradigm

Segmental patterns of yers

Vocalized yer quality

| Language | *sъnъ ‘dream’ | *dьnь ‘day’ | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ukrainian | son | den’ | ь > e, ъ > o |

| Russian | son | d’en’ | ь > e + C’, ъ > o |

| Belarusian | son | dz’en’ | ь > e + C’, ъ > o |

| Upper Sorbian | són | dźeń | ь > ɛ + C’, ъ > ɔ |

| Lower Sorbian | seń | źeń | ь > ɛ + C’, ъ > ɛ/a |

| Polish | sen | dzień | ь > ɛ + C’, ъ > ɛ |

| Slovak | sen | den | ь > ɛ + C’, ъ > ɛ (but see note) |

| Czech | sen | den | Almost full merger |

| Bulgarian | sъn | den | ь > e, ъ > ъ |

| Macedonian | son | den | ь > e, ъ > o |

| BCMS | san | dan | Full merger |

| Slovenian | sən | dan | Full qualitative merger |

A typology of yer outcomes

| Vowels alternating with zero | Difference in consonant behaviour | Languages |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple | Yes | Russian, Belarusian, Sorbian: [ɛ ɔ] |

| Slovak: [ɛ ɔ ɑ ɑː i͡e] | ||

| Multiple | No | Bulgarian: [ъ ɛ] |

| Macedonian: [ɛ ɔ] | ||

| Ukrainian: [ɛ ɔ] | ||

| Slovenian: [ə aː] | ||

| One | Yes | Polish: [ɛ] (marginally [ɔ]) |

| One | No | Czech: [ɛ] |

| BCMS: [a] |

Preliminary summary

What does any theory of yers need to explain?

- Why do some vowel alternate with zero and others don’t?

- How do know when to vocalize and when to delete?

- When the yer vocalizes, what quality does it have?

Previous approaches

The Lower rule

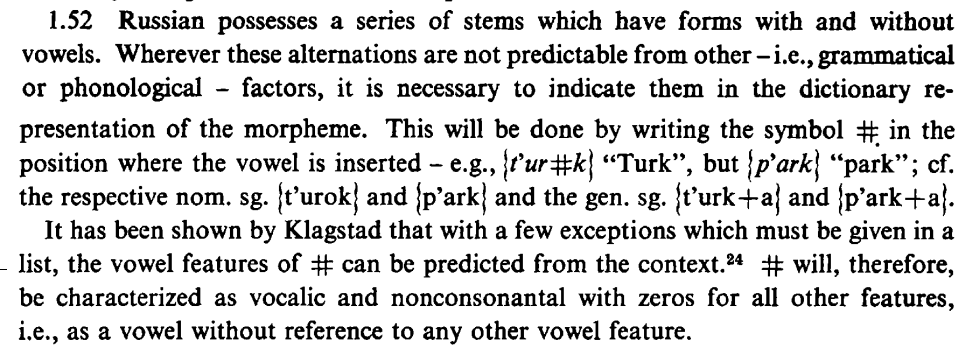

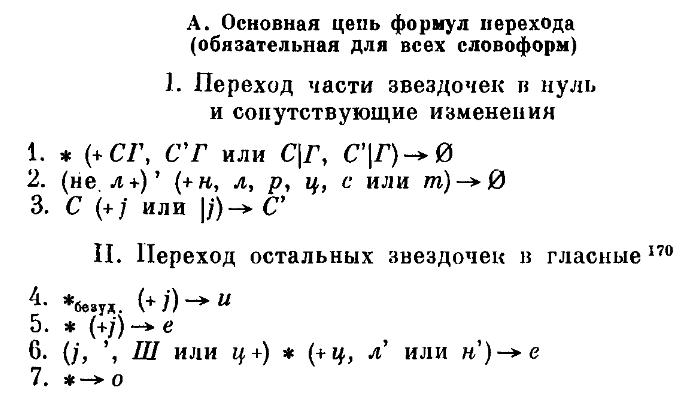

Lightner (1965): the Lower rule for Russian

ĭ ŭ \(\rightarrow\) e o / _ C\(_0\) {ĭ ŭ}, applying left to right

The effect is that all yers before a yer vocalize, but the last yer in a sequence, or a yer before a non-yer vowel, do not and can eventually be deleted

The front yer is a normal front vowel and can do everything that front vowels do:

- Palatalize preceding consonants

- Undergo backing once it has merged with /ĕ/

Some Russian derivations

| Rule | /dĭn+ĭ/ | /dĭn+ī/ | /dĭn+ĭk+ŭ/ | /dĭn+ĭk+ĭk+ŭ/ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palatalization | dʲĭnʲĭ | dʲĭnʲī | dʲĭnʲĭkŭ | (dʲĭnʲĭk)ĭkŭ |

| Lower | dʲĕnʲĭ | dʲĭnʲī | dʲĕnʲĕkŭ | (dʲĕnʲĕk)ĭkŭ |

| Backing | dʲĕnʲŏkŭ | (dʲenʲŏk)ĭkŭ | ||

| Palatalization | dʲĕnʲŏčʲĭkŭ | |||

| Lower | dʲĕnʲŏčʲĕkŭ | |||

| Yer deletion | dʲĕnʲ | dʲnʲī | dʲĕnʲŏk | dʲĕnʲŏčʲĕk |

| Late rules | dʲenʲ | dnʲi | dʲenʲok | dʲenʲočʲek |

| Gloss | ‘day-NOM’ | ‘day-PL’ | ‘day-DIM-NOM’ | ‘day-DIM-DIM-NOM’ |

Extending the analysis: Polish

| Rule | /sOn+O/ | /sOn+ɨ/ | /dEn+E/ | /dEn+i/ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palatalization | dʲEnʲE | dʲEnʲi | ||

| Lower | sɛnO | sOnɨ | dʲɛnʲE | dʲnʲi |

| Yer deletion | sɛn | snɨ | dʲenʲ | dʲnʲi |

| Late rules | sɛn | snɨ | d͡ʑɛɲ | dɲi |

Further evidence: secondary imperfective ablaut/tensing

| Vocalized yer | Weak yer | Imperfective | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|

| zapiąć [pʲɔɲ] | zapnę | zapinać | ‘fasten’ |

| nadąć [dɔɲ] | nadmę | nadymać | ‘inflate’ |

Summary of the classical approach

- Why do some vowel alternate with zero and others don’t?

They are featurally different in the underlying representation

- How do we know when to vocalize and when to delete?

The Lower rule is sensitive to the features of vowels in the following syllable

- When the yer vocalizes, what quality does it have?

Determined by the Lower rule

Autosegmentalizing Lower

With the advent of autosegmental phonology, the property of ‘alternating with zero’ could be encoded by means other than segmental features

Autosegmental Lower with defective representations

What does this get us?

- Any vowel can be a yer: East Slavic, Sorbian, especially Slovak (Rubach 1993), even Polish

- No special ‘yer subinventory’: yers are featurally regular

- What is special about yers is prosodic position

- CVCV phonology: alternation with zero follows from first principles

- CVCV phonology: clearly articulated link with phonotactics

Phonotactics, deletion, and insertion

Deletion or insertion?

In principle, vowel-zero alternations can be due to either deletion or insertion

- The standard account relies on deletion

- Why not insertion? Two reasons

- Phonotactics

- Vowel quality

Insertion and phonotactics

- Insertion could be driven by

- Avoidance of bad sonority profiles

- Avoidance of consonant clusters (at word edges) tout court

Yers and cluster avoidance

- Classic examples aiming to show an absence of general cluster avoidance

- Russian laska ‘stoat’ ~ lasok ‘GEN.PL’ vs. laska ‘tenderness’ ~ lask ‘GEN.PL’

- Russian z’erno ‘grain’ ~ z’or’en ‘GEN.PL’ vs. s’erna ‘chamois’ ~ s’ern ‘GEN.PL’

- Polish trumna ‘coffin’ ~ trumien vs. kolumna ‘column’ ~ kolumn ‘GEN.PL’

- Slovak octu ‘vinegar.GEN.SG’ ~ ocot ‘NOM.SG’ vs. pocta ‘distinction’ ~ pôct ‘GEN.PL’

Yers and sonority profiles

- Classic examples showing that suboptimal sonority profiles are tolerated

- Russian t’eatr ‘theatre’, os’otr ‘sturgeon’

- Polish wiatr ‘wind’, cyfr ‘figure.GEN.PL’

However…

- In BCMS1 only coronal fricative-stop clusters are allowed word-finally

- Everything else is broken up by a vowel, leading to alternations

- The only vowel involved is [a]

- vjetar ~ vjetru ‘wind’ like sladak ~ slatki ‘sweet’

- There is a plausible insertion analysis

Sonority and epenthesis

- BCMS vjetar ‘wind’, oštar ‘sharp’ ~ vjetri, oštri

- Bulgarian ogъn ‘fire’, ostъr ‘sharp’ ~ ogn’ove, ostri1

- Russian v’et’er ‘wind’, ogon’ ‘fire’, v’ód’er ‘bucket.GEN.PL’ ~ v’etrɨ, ogn’i, v’ódra (Isačenko 1970)

- On the other hand, m’etr ‘metre’

Why not both?

| Language | UR | NOM.SG | GEN.SG | DIM | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polish | /t͡sɨfr/ | cyfra | cyfr | cyferka | ‘figure’ |

| /srebEr/ | srebro | sreber | sreberka | ‘silver’ | |

| Russian | /igl/ | igla | igl | igolka | ‘needle’ |

| /kukOl/ | kukla | kukol | kukolka | ‘doll’ |

A prediction

When a vowel is inserted, its quality should be predictable

Yers and predictability: Russian

Is yer quality predictable?

- Scheer (2011) passim, and many others: no

| Context | e | o |

|---|---|---|

| Cʲ_ | d’en’ ~ dn’a ‘day’ | l’on ~ l’na ‘linen’ |

| C_ | * | son ~ sna ‘dream’ |

Zaliznyak (1967): yes (essentially)

The return of the mid vowel alternation

- After a hard consonant, the yer is always [o]

- After a soft consonant, the yer is either [e] or [o]

- In the classical analysis, this is backwards: the soft consonant is soft because the yer is front

- The sequence [Cʲo] from /Cĭ/ arises by the sequence of Palatalization > Lower > Backing

An alternative

So, unpredictable after all?

- Yesterday we developed an account of the e ~ o alternation mostly allowed us to cope with exceptionality

- Two classes of mid vowel after [Cʲ]

- [e] before a softening suffix, [o] elsewhere

- Non-alternating [e]

- It turns out that when a vowel alternates with zero, it is overwhelmingly type 1

- The exceptions are either conditioned (before j c l’ n’)1 or tiny in number: in the nouns, there is a total of five exceptions (Zaliznyak 1967; Iosad 2020). I can live with that.

Summing up

- The quality of Russian yers is mostly predictable if

- We take into account the softness of the preceding consonant

- We adapt our analysis of mid vowels: when the right context drives the choice, the front outcome is conditioned and the back outcome is the elsewhere

- We still (mostly) cannot predict when the vowel is inserted or not

Conclusion

Why does this matter?

- The analysis relies on consonant softness being present before yer quality is resolved: ‘consonant power’

- This is incompatible with the classical account, where the consonant is soft because the yer is front: ‘vowel power’

- Who is right?

Consonant power revisited

- In the consonant power approach

- Consonant softness can be underlying

- Palatalization is not a sure-fire sign of an underlying front vowel

- Repeated attempts to resurrect this in the generative tradition (Farina 1991; Boyd 1997; Padgett 2011) have not been too influential

- Vowel power continues to rule the roost (Halle & Matushansky 2002; Rubach 2000; Rubach 2005; Rubach 2016)

One final prediction

Scheer (2012): ‘if a vowel is epenthetic, its quality cannot be contrastive’

| NOM.SG | GEN.PL | Derivative | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|

| igla | igl | igólka | ‘needle’ |

| iskra | iskr | ískorka | ‘spark’ |

| nasmork | násmoročnɨj | ‘cold’ | |

| pol’za | pol’z | pol’éznɨj | ‘useful’ |

| vojna | vojn | vojénnɨj | ‘war’ |

| korabl’ | korab’él’nɨj | ‘ship’ | |

| s’el’d’ | s’el’ódka | ‘herring’ |

- The vowels are not yers — but they follow the generalizatons quite precisely

- The softness of the consonants determines the quality of the vowels, not the other way around

What’s next?

Tomorrow, we reconsider the status of the historically informed traditional approach.