The rise, fall and rise of contrast

Outline

- The rise of phonology and the rise of contrast

- The fall of contrast in generative phonology

- The return of underspecification — and eventually contrast

Contrast rules the roost

Contrast and the phoneme

The phoneme is the minimal unit that makes lexical distinctions in a language

…or something like this. This is the textbook definition, but why should lexical distinction matter?

Prague School phonology

Schallgegensätze, die in der betreffenden Sprache die intellektuelle Bedeutung zweier Wörter differenzieren können, nennen wir phonologische (oder phonologisch distinktive…) Oppositionen. Solche Schallgegensätze dagegen, die diese Fähigkeit nicht besitzen, bezeichnen wir als phonologisch irrelevant oder indistinktiv

…das Phonem [ist] die Gesamtheit der phonologische relevantent Eigenschaften eines Lautgebildes

These are the definitions from Trubetzkoy (1939), the founding text of Western structuralist phonology.

What we should notice is that he is basically defining distinctiveness as being what the phonology is about: anything that is not distinctive is not phonology. Therefore, if the property of a sound does not contribute to contrast within the language, it is not phonological — or, rather, not phonemic.

This is, in a nutshell, The Contrastivist Hypothesis (Hall 2007)

What does this mean in practice?

Let’s take what is1 ‘the same’ sound [r]. What is the status of the property of ‘r-ness’ (rhoticity)?

1 Roughly, don’t @ me.

The idea that knowing what a sound is like is not enough to know how it is represented in the grammar is the basic idea of Western phonology, usually ascribed to the Kazan School. This is the Praguian fleshing out of the basic idea.

| Word | Gloss | Word | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|

| kal | ‘will go’ | iɾɯmi | ‘name’ |

| ilkop | ‘seven’ | kɯrəm | ‘then’ |

| onɯlppəm | ‘tonight’ | kaɾiɾo | ‘outside’ |

| pal | ‘foot’ | uɾi | ‘we’ |

| pʰal | ‘arm’ | saɾam | ‘person’ |

- [ɾ] occurs intervocalically

- [l] occurs elsewhere

- Rhoticity of [r] is not phonemic (= ‘not phonological’)

- There is a liquid phoneme (probably /l/), with [ɾ] its conditioned allophone

- Korean /l/ is a non-nasal sonorant

Phonemic rhoticity: English

- rip ≠ lip

- row ≠ low

- peer ≠ peal (for some accents)

‘Being rhotic’ is a phonologically relevant property of English [r]

…but that’s sufficient to pick [r] out of English consonants

- English /r/ is a non-nasal, non-lateral sonorant

A different kind of phonemic rhoticity: Czech

- Some minimal pairs

- radit ≠ ladit, rak ≠ lak

- řadný ≠ žadný

- řada ≠ rada

- Is Czech r a non-nasal non-lateral sonorant?

Yes, but so is ř!

Czech r is a non-nasal, non-lateral, non-fricative sonorant

More different rhoticity: Nivkh

| Manner | Labial | Dental | Palatal | Velar | Postvelar |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stops | pʰ p | tʰ t | cʰ c | kʰ k | qʰ q |

| Fricatives | f v | s z | x ɣ | χ ʁ | |

| Nasals | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | |

| Approximants | w | l r r̥ | j | h |

Nivkh r is a non-nasal, non-lateral, voiced sonorant

Except…

Nivkh r isn’t really a sonorant (which Trubetzkoy already knew)

| ‘lose’ | ‘house’ | ‘bring’ | ‘bear’ | ‘destroy’ | ‘fox’ | ‘save’ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unmutated | pəkz | təf | tʰəpr | cʰxəf | cosq | kʰeq | kəlŋu |

| Mutated | vəkz | rəf | r̥əpr | sxəf | zosq | xeq | xəlŋu |

Actually, Nivkh [r] is an unaspirated dental fricative

Is this a problem?

- This suggests that perhaps the set of contrasts is not the only thing determining how we analyse the phonology of a language

- Here, we see the first intimations of the idea that patterning matters

- This was to be the downfall of contrast

Moving away from contrast

Why would you abandon this idea?

Three (putative) reasons:

- Indeterminacy of analysis (we will return to this on Wednesday)

- Rise of universal feature theory

- Loss of generalization

Contrast and feature theory

- For Trubetzkoy (1939), phonemic status was ascribed to ‘sound distinctions’

- Actually most of Trubetzkoy (1939) is a straight up typological survey of what kind of distinctions show up as phonemic in different languages

- Theoretically, the ‘properties’ were reified as ‘correlations’ existing between phones

- The phone (‘segment’) comes first, correlations come later

- Jakobson, Fant & Halle (1951) and much subsequent work: distinctive features

Distinctive features

- Closed (smallish) list

- Binary (+ or - values)

- Defined by non-language-specific criteria

- Properties of the acoustic signal (Jakobson, Fant & Halle 1951; Halle 1959)

- Articulatory labels (Chomsky & Halle 1968)

In the distinctive-feature world, features come first, segments are epiphenomenal.

A major consequence is that we are now able to define, or talk about the properties of, segments without any reference to other elements of the system. What is the place of the contrast criterion in this universe

Allophonic alternations: English

| Phoneme | Word-final | Pre-dental | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| /n/ | ten [tʰɛn] | /tɛn/ | tenth [tʰɛn̪θ] | /tenθ/ |

| /l/ | cool [kʰʉl] | /kul/ | coolth [kʰʉl̪θ] | /kulθ/ |

- The morphemes ten, cool have two phonologically conditioned allomorphs, one with a final alveolar and one with a final dental

- There is an alternation between [n l] and [n̪ l̪]

- However, phonemically ten and cool

Neutralizing alternations: Russian final devoicing

| Item | NOM.SG | GEN.SG |

|---|---|---|

| ‘fate’ | rok | roka |

| ‘horn’ | rok | roga |

| ‘cat’ | kot | kota |

| ‘code’ | kot | koda |

- The alternations are [t k] ~ [d g]

- But /t k/ are different phonemes from /d g/, as shown by the (near-)minimal pairs in the second column

- So here we have an alternation between two phonemes

‘Phonemic overlapping’

Bloch (1941): American English

- Pre-voiced lengthening: bit beat bat vs. bid bead bad [ɪ i æ] vs. [ɪː iː æː]

- The distribution is allophonic

- bit /bɪt/ and bid /bɪd/ have the same phoneme

- Low vowels: bomb bother sorry [ɑ] vs. balm father starry [ɑː]

- /ɑ/ and /ɑː/ are phonemic

- bomb /bɑm/ does not have the same phoneme as balm /bɑːm/

- Now try pot pod [pʰɑt pʰɑːd]

- Is it like bit bid or like bomb balm?

Most structuralist frameworks2 accept that the vowel of pod [pʰɑːd] has no relation to that of pot [pʰɑt], even though they are clearly related in the exact same way as the vowels of bit and bead.

2 But not all! See in particular the Moscow School of phonology

This leads them to consider neutralizing alternations like Russian final devoicing also involve different phonemes, which are not related in any way clear way.

What’s the problem though?

Bloch’s ‘phonemic overlapping’ does not involve alternations, but some other examples do

Famously, Russian (see Anderson 2000)

| Gloss | Word-final | Prevocalic | Assimilation context | Alternation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ‘cat’ | kɔt | kɐˈtˠi | kɔd bˠi | /t/ ~ /t/ ~ /d/ |

| ‘code’ | kɔt | ˈkɔdˠi | kɔd bˠi | /t/ ~ /d/ ~ /d/ |

| ‘night’ | nɔt͡ʃʲ | ˈnɔt͡ʃʲi | nɔd͡ʒʲ bˠi | /t͡ʃʲ/ ~ /t͡ʃʲ/ ~ /t͡ʃʲ/ [d͡ʒʲ] |

- For /t/ ~ /d/, the alternation is phonemic

- For [t͡ʃʲ] ~ [d͡ʒʲ], the alternation is allophonic

- But it is clearly the same alternation

What does this have to do with contrast?

- Structuralist phonology started with the premise that some distinctions can be more important than others in the language

- If we want to capture the full generalization, that distinction does not correspond to anything useful

- Therefore, we should ignore the distinction

- The distinction came from thinking about contrast, so privileging contrast was a mistake

Contrast returns

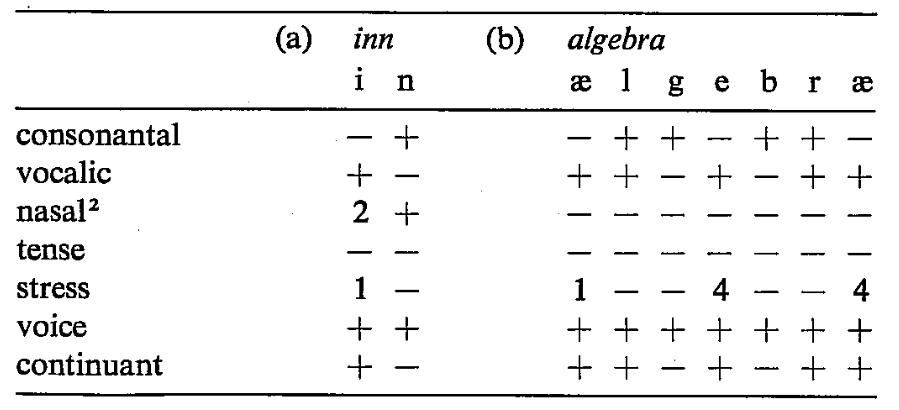

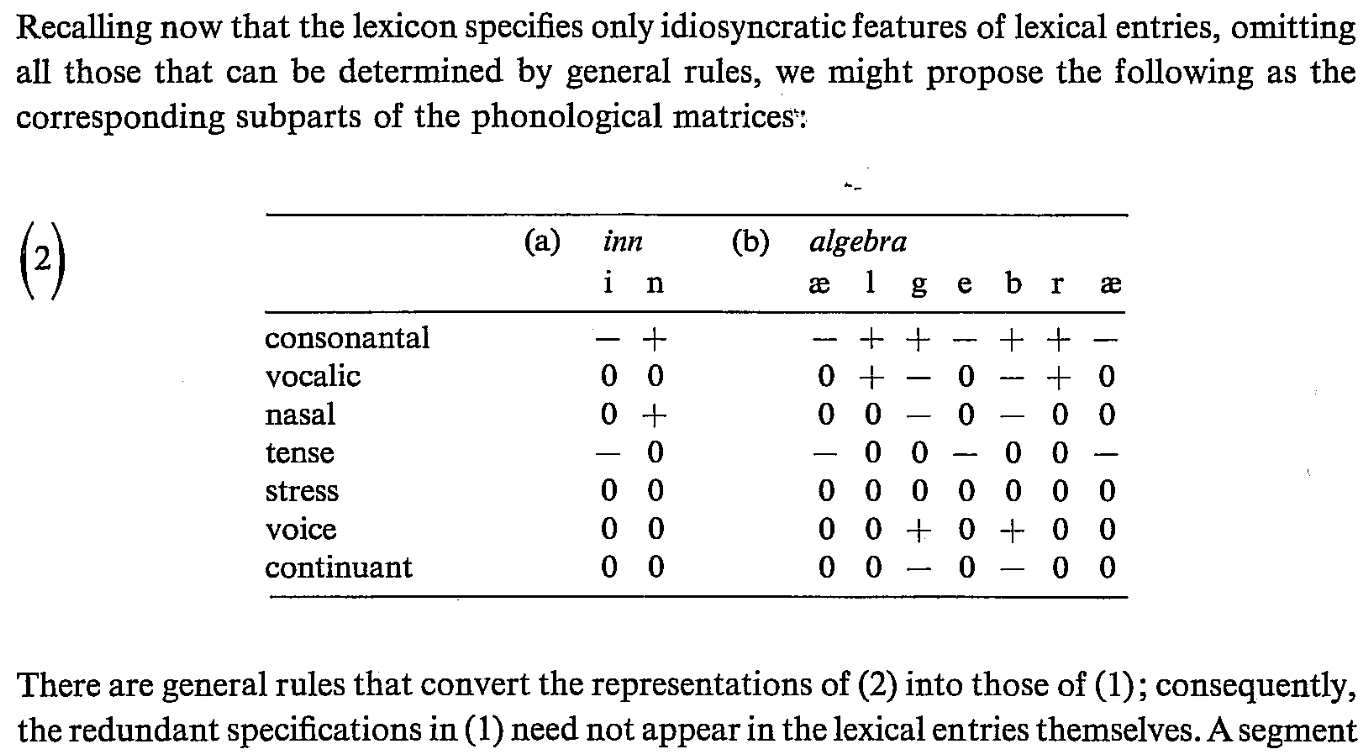

Mainstream post-SPE position

- Phonological representations are strings of segments (and boundary markers, junctures…)

- A segment is a shorthand for a set of binary feature values

- In the phonological grammar, every segment is (ideally) fully specified for all features3

- Predictable aspects of sound patterns should be captured by rule

3 We return to the detail of this tomorrow

Tender spots: predictability

- Ultimately, contrast is an example of unpredictability

- Allophony: given English [s_ɪn], do you fill in the blank with [pʰ] or [p]?

- Contrast: given English [_ɪn], do you fill in the blank with [pʰ], [tʰ], or [kʰ]?

Inherent redundancy

As we know, not all features of a segment contribute to contrast — many are predictable from the contrastive features

The predictable feature values are inserted by redundancy rule

Explaining phonotactic patterns

- If you know this is a word of English, can you fill in the missing features?

| ɪ | ŋ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| -syl | -syl | -syl | +syl | -syl |

| +son | +son | |||

| +hi | -cor | |||

| -bk | -ant | |||

| -rd | +nas | |||

| -tns |

As we know from John’s course, the only allowable CCC onsets in English are /s/ + stop + non-nasal sonorant. So at least some of the features here are predictable; in the extreme case of /s/, once we know it is a consonant in this position, we can fill in all the features. The difference from the preceding case is that the redundancy is contextual.

But predictable aspects of sound structure should be done by a rule — or at least they should not be stored. So we could just leave these predictable features unspecified and fill them in by rule.

Solutions?

The usual approach is to have a component pre-phonology that is responsible for filling in this predictable information:

- Morpheme structure constraints

- Markedness conventions (more tomorrow)

- Redundancy rules

Lexical Phonology and Morphology

- Lexical rules

- Interacts with morphology

- Interacts with the lexicon

- Possible cyclicity

- Derived environment effects

- Sustain exceptions

- Postlexical rules

- Follow postlexical rules

- Do not show the ‘lexical syndrome’

Phonology and the lexicon

- One aspect in which lexical rule ‘interact with the lexicon’ is that conditions placed in the pre-phonology can remain active in the lexical stratum

- But not postlexically

- ‘Marking condition’ in the English lexicon: [*αvoi,+son]

- Lexical devoicing rule: adze, apse, *[ds], *[pz], width

- Does not apply to sonorants: pint [nt]

Structure Preservation

- Kiparsky (1985)

- Marking condition remains active in the (lexical) phonology and forces sonorants to keep their ‘blanks’ for longer

- But the blanks arise from lexical contrastiveness in the first place!

- So we are smuggling contrast back into the phonology

Tomorrow

- We will see how this plays out technically on Wednesday

- Before that, we need to think about markedness